[Guest post by Grace Bauer, Co-Director of Justice 4 Families]

In what feels like another lifetime…

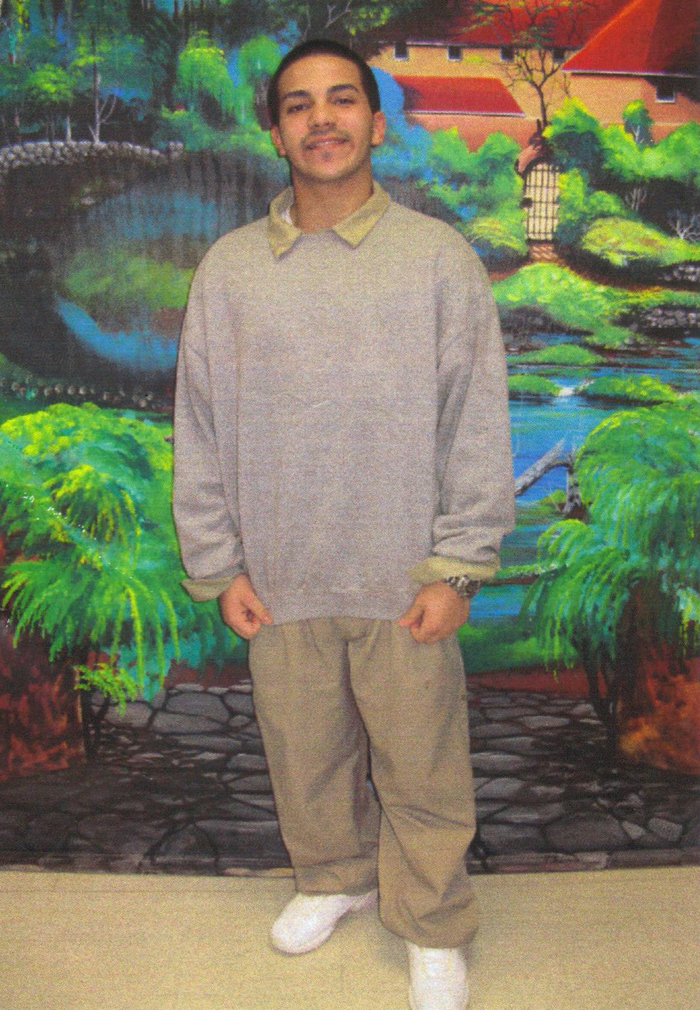

It was summer and we decided to take the kids and my mom fishing. My son wanted to bring his new bike with the training wheels. As soon as his dad took it out of the truck, he was off. Happy to have a big place to ride, he had a smile from ear to ear.

A little while passed and he asked his dad to take the training wheels off. Once the wheels were off, his dad held on to the back to steady the bike and he began pedaling. It didn’t take long for him to tell his dad that he could do it and dad should let go. I held my breath and his dad held on for a minute longer, despite his protests. Dad was running behind him and then he stopped. He was right! He could do it! Off he went, pedaling like mad, red hair blowing in the wind, yelling the whole time, “I’m doing it! I’m riding my big boy bike!”

...

[aside title="Sign the ACLU Petition to end juvenile solitary confinement"] ACLU Action: A Mother's Plea: Stop Solitary Confinement of Children[/aside]Solitary confinement, or isolation, is widely used around the country in jails, prisons and detention centers for adults as well as young people. Until very recently, few people, beyond attorneys, families and advocates, gave it much thought. Isolation, like so many corrections practices, happens behind the walls of silence, long ingrained into facility culture and practice. In our punishment-oriented society, we tend to think those behind bars deserve whatever they get. This kind of thinking is fueled by a distorted sense of fear created by media and political rhetoric so much so that falling crime rates and research showing the failure of such practices barely register in society’s consciousness.

When a young person enters into secure detention, they typically become isolated from their families and communities. Exorbitant phone costs, limited visitation procedures and times and placement in facilities long distances from home all add to that sense of isolation. Often, facilities will have a standard 2-6 week “intake” period where the child is not allowed any visitors and very limited communication by phone. Given that the majority of children involved in juvenile justice systems come from families who live below the poverty line, many families do not have transportation to reach far away facilities or the extra money to cover the cost of calls that experts describe as “gross profiteering.” These are common practices in detention that fail to take into account the research that demonstrate the critical importance, of maintaining family and community connections, to the successful reentry of young people and to prevent recidivism.

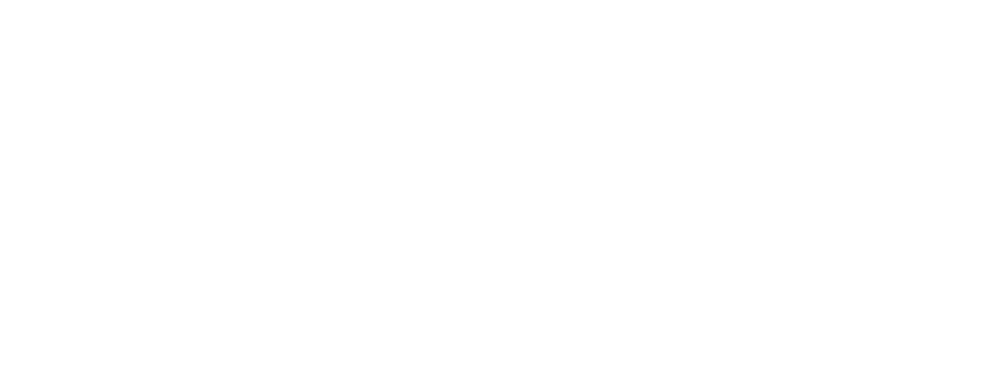

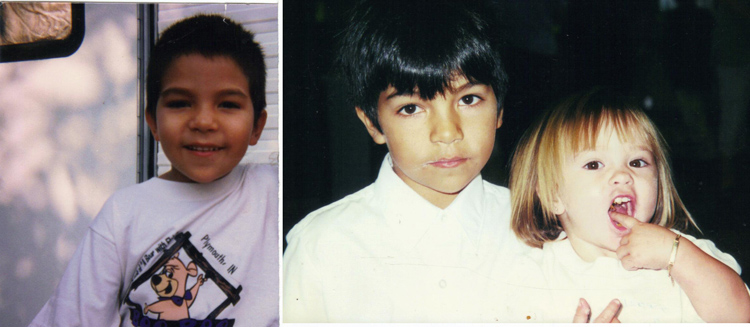

My son is 25 years old. He has spent the majority of the last 15 years in detention centers, youth prisons, county jails and state prisons. His sisters have grown up, his niece was born and will celebrate her sixth birthday, our home was lost in a hurricane, a new home was built, his sister started college (and will graduate) and his uncle died, all while he was confined. He earned his high school diploma but has few job skills, little job experience, no home, no family of his own, few friends and few prospects on the horizon. We have missed him and his presence in our lives and he has missed life, period.

He will return to society, at some point, along with roughly 800,000 others released each year; 95% of all sentenced inmates. The “tough on crime” rhetoric may make folks feel better but the reality of mass incarceration impacts everyone in society through lost revenues, increased health cost, lower wages, unemployment, expensive corrections and judicial budgets-- the list goes on and on. As facilities cut back on the very things that lead to successful reentry, we can expect that young people, returning to society, will return less prepared, more disadvantaged and more deeply scarred.

All of the above and then we add on the deep psychological damage of solitary confinement. During this video, you can see how isolation looks during a 24- hour period. You are able to watch the entire day pass in mere minutes. From the outside looking in, especially in this condensed version, you might believe that isolation isn’t that bad. In fact, for those of us living in a high tech, ever-connected world, 24 hours of being disconnected might seem like a welcome relief from the endless text messages, calls, voice mails, email and social media alerts! Before you volunteer yourself, lets think about this from the inside looking out.

When my son was 13 and placed in a notorious juvenile prison, he spent nearly a year in protective custody, AKA solitary confinement. In those early days we had no information on the damaging effects of solitary and actually felt relief that he felt safe from the rampant violence in the facility. He was released from state secure care in 2002; four years would pass before we learned the truth about his time in isolation. It should have been evident that something traumatic and life changing had happened and we certainly saw the signs of something but we didn’t know what. In 2006, a young man confined with him at the youth prison called to tell us about the day my son was raped by another young person, in solitary, who had been placed in the cell by guards. Those guards then took bets on which “kid would win”. My son lost the fight that day. Throughout his years of incarceration, he has experienced solitary confinement in every facility, often for extended periods of time.

[aside title="Sign the ACLU Petition to end juvenile solitary confinement"] ACLU Action: A Mother's Plea: Stop Solitary Confinement of Children[/aside]

I clearly remember the call from my son. “Mom, this can’t be legal. This is so wrong! I can’t believe they are doing this to this man.” This from a young man that never complains about his own stark living conditions, poor treatment, the brutality that is inflicted on him or that he witnesses almost daily or the arbitrary enforcement of rules. His concern during that call was for another man being held in solitary. This man, who was a little older than my son, was quite obviously mentally ill. My son was afraid for this man’s life. He told me about the man’s behavior over the last few days, including banging his head on the bars and floor hard enough to knock himself out and needing stitches to close wounds, screaming for hours until he was too hoarse to scream anymore, crying uncontrollably for hours, threatening to kill himself and talking to people who weren’t there during hallucinations. My son, the “criminal”, called me to see if I could find help for this man because he was very concerned that the man was going to hurt himself or take his own life and he felt like the facility staff were ignoring how serious this situation actually was.

From January 25th through May 8th of this year, my son was confined in isolation, though the prison called it “protective custody.” He was confined for 110 days with the exception of being allowed to take a shower on Monday and Thursdays and use the phone at midnight or later. Several of his showers and calls were denied for unknown reasons. The average call lasted 6 minutes. That means that over a 110-day period my son showered approximately 30 times and was able to speak with us for about 3 hours. In this particular case, my son was confined for his own safety after being stabbed three times during the robbery of his cell. As his mother, I am grateful that he was kept safe and at the same time, terribly troubled by this prolonged period of isolation and its impact on his mental health.

[feature href=”https://www.juvenile-in-justice.com/take-action” buttontext=Go!”] Ready to take action against juvenile isolation? [/feature]

I have witnessed the long-term impact of my son’s time in isolation and prison. Some nights when I try to sleep, visions of the assaults play in my mind, like a movie that you can’t turn off. I have sat across from him, trying to maintain my own composure, while mentally cataloging and assessing the bruises and wounds on his body. I have waited for calls or visits where I can know, at least for a short time, that he is safe and alive. I listen to him talk about how useless he is and how he has no worth. I held back tears (at least, in his presence) the day he said, “I’ll never be anything but a criminal.” In the car, on the way home, I cried like a child, as I thought of all the good in him and the future I had once dreamed of for him. The level of violence and inhumanity that he endures sickens me. Sometimes, when I can’t hold it off any longer or we experience a new trauma, I cry hard and long for all that he has lost, all we have lost and how far we still have to go.

Day in and day out, we look for ways to keep him up-to-date on the world and engaged in learning. I marvel at his continued compassion and concern for strangers in such circumstances. His belief that, someday, he will finish serving his time and somehow overcome the numerous and complex barriers he faces inspires me. If he can still feel hopeful, I’ll be damned if I will be the one to take that from him.

Once, he was an honor roll student that was well liked by his teachers and peers. After a few short months in juvenile detention he became fearful and anxious. I could not touch him to wake him up. He would strike out blindly in his waking moments out of fear of being assaulted. He cried out in his sleep and suffered from nightmares. He was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and deep depression. The physical abuse has left him with physical scars but it is the emotional damage, caused by the extreme isolation and exposure to horrific violence at such a young age, that concerns me the most.

My son’s original crime was stealing a stereo out of a truck and breaking the window out of the truck. He was sentenced to five years for that crime. We were fortunate to find an attorney to represent him and get him out after a year. Unfortunately, the damage done in that year was enough to alter his life in ways I could not have imagined. He was grieving for his beloved grandmother and acted out, as adolescents often do in those tumultuous years. The vicious assaults on his body, severe neglect and emotional and verbal abuse he suffered would be considered criminal if I or anyone else, other than the system, had inflicted them upon him. Yet the state and its employees were allowed to do this kind of harm to him and to thousands of others and there has never been any accountability for those crimes.

Behind the razor wire fences of America’s prisons, there is seldom fair redress of grievances, little accountability to the safety and wellbeing of those housed within those facilities, scant programming, meager education services, woefully inadequate healthcare, widespread racial disparities and the pervasive and systemic abuse of power by those in authority. Study after study, report after report, all confirm the negative impact of isolation and the abject failure of mass incarceration. The cost benefit analysis, illustrated in volumes of data and research, demonstrate the exorbitant cost we pay to have less public safety, generate more crime and do unnecessary and possibly irreparable damage to those behind bars.

Prisons were supposedly built to lock up those who might harm others and deter crime. Somewhere along the way we lost sight of those goals. Today, prison walls have become an impenetrable shroud that shields and perpetuates crimes against humanity. Those walls allow the rest of us to ignore the root causes of crime and save us from having to look at the mass destruction of human lives that our appetite for retribution and punishment have caused.

Grace Bauer is the Co-Director of Justices For Families, a respected leader and a trusted confidant for families seeking justice across the country, and the mother of three children from Sulphur, Louisiana.

Last week, we brought you inside Santa Maria Juvenile Hall to meet

Last week, we brought you inside Santa Maria Juvenile Hall to meet

Cheryle:

Sometimes I wish we had left the country. We had that weekend, we could have run away. But we had no idea. We knew he was innocent. We went on vacation. We were so naïve. I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen. Looking back, there were so many things I would have done differently. But you can’t go back. It was the first time we’d been involved in the juvenile justice system. We hired a lawyer we heard was very good. We paid a fortune. My daughter sold her house to pay for him. He let us down immensely.”

[superquote]I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen.[/superquote]

One of my biggest regrets, since we were all going to testify as witnesses, we couldn’t be in the court during Anthony’s proceedings. We waited in the hall every day, waiting to go in, waiting to hear news. Since we weren’t in the room, we couldn’t know exactly how bad our lawyer was.

The juror selection was completely unjust: how was it that when I looked across the room at the jury pool I recognized so many faces? Lake County is HUGE, why couldn’t they pull a more diverse selection of jurors? One of the jurors was from our little community. He was an Elk’s Club member. His wife and the prosecutor’s mother knew each other. This juror gave another juror a ride home to Whiting each day, discussing the case in the car. The trouble with this juror began when he was first selected. He was a neighbor of a niece; it was not a friendly relationship. We knew that it would be wrong for him to be on the jury. My daughter wrote a note during jury selection and asked our lawyer not to allow this juror on the jury. The Judge saw the note being passed to the lawyer and called him to the bench she asked him if there was a problem with the juror and he said, “we already picked him.” A witness came to us during the trial and said they had seen yet another juror hugging a member of the dead boy’s family. We were told by our lawyer, “don’t bring these things up it will anger the Judge.” An alternate juror was so outraged by what had taken place in the jury deliberation, she called our lawyer crying. She told us how jurors were convinced to change their votes to guilty. How the evidence that was used to convict Anthony was that he wore a school uniform and there was someone seen in the area wearing a uniform. The school was a couple blocks way; there must have been many kids in the area in uniform. The other so-called evidence was that he was not on the phone for 17 minutes that afternoon. The prosecutor said in his closing arguments that the murder took 17 minutes. How would he know how long it took to murder this poor boy? There were other times throughout the day that Anthony had not been on the phone. When he came to my house I made him get off the phone to talk to the family. This was not evidence; this had nothing to do with the murder. The DNA is not Anthony’s. The eye witness said it wasn’t Anthony.

Cheryle:

Sometimes I wish we had left the country. We had that weekend, we could have run away. But we had no idea. We knew he was innocent. We went on vacation. We were so naïve. I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen. Looking back, there were so many things I would have done differently. But you can’t go back. It was the first time we’d been involved in the juvenile justice system. We hired a lawyer we heard was very good. We paid a fortune. My daughter sold her house to pay for him. He let us down immensely.”

[superquote]I used to believe in the system. Now I am angry with myself for believing. Devastated that something like this can happen, does happen.[/superquote]

One of my biggest regrets, since we were all going to testify as witnesses, we couldn’t be in the court during Anthony’s proceedings. We waited in the hall every day, waiting to go in, waiting to hear news. Since we weren’t in the room, we couldn’t know exactly how bad our lawyer was.

The juror selection was completely unjust: how was it that when I looked across the room at the jury pool I recognized so many faces? Lake County is HUGE, why couldn’t they pull a more diverse selection of jurors? One of the jurors was from our little community. He was an Elk’s Club member. His wife and the prosecutor’s mother knew each other. This juror gave another juror a ride home to Whiting each day, discussing the case in the car. The trouble with this juror began when he was first selected. He was a neighbor of a niece; it was not a friendly relationship. We knew that it would be wrong for him to be on the jury. My daughter wrote a note during jury selection and asked our lawyer not to allow this juror on the jury. The Judge saw the note being passed to the lawyer and called him to the bench she asked him if there was a problem with the juror and he said, “we already picked him.” A witness came to us during the trial and said they had seen yet another juror hugging a member of the dead boy’s family. We were told by our lawyer, “don’t bring these things up it will anger the Judge.” An alternate juror was so outraged by what had taken place in the jury deliberation, she called our lawyer crying. She told us how jurors were convinced to change their votes to guilty. How the evidence that was used to convict Anthony was that he wore a school uniform and there was someone seen in the area wearing a uniform. The school was a couple blocks way; there must have been many kids in the area in uniform. The other so-called evidence was that he was not on the phone for 17 minutes that afternoon. The prosecutor said in his closing arguments that the murder took 17 minutes. How would he know how long it took to murder this poor boy? There were other times throughout the day that Anthony had not been on the phone. When he came to my house I made him get off the phone to talk to the family. This was not evidence; this had nothing to do with the murder. The DNA is not Anthony’s. The eye witness said it wasn’t Anthony.

[superquote]Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now.[/superquote]

Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now. My granddaughter, Anthony’s little sister, hasn’t been getting enough attention from us. She got lost in all of this. She told one of her friends at school about the whole thing and the parents of the friend forbid their friendship. So she just holds it in, doesn’t tell anyone for fear of reprisal. I have started homeschooling her. She was being bullied. I woke up one morning and realized that whatever energy I had left needed to go towards helping her. She sees a counselor now. At first she didn’t want to visit Anthony, she was scared and so young. But now she visits. We bring in all the kids: the cousins, my 3-year-old grandson, Anthony loves him. Some people question why we bring them in. But they have a right to know each other. He didn’t do anything wrong. Grace [Bauer, of Justice For Families] says you have to do things however you see fit, whatever works for your family. Anthony loves the kids. He talks about driving a car and having kids of his own someday.”

After The Sentencing

“We had a Writ of Cert that was reviewed and denied by the Supreme Court on November 30th. Getting the Writ cost us $8,500.00. My daughter already sold her house, so she sold her car. This should be a right for EVERYONE. It should not be this cost-prohibitive. At least we have these things to sell. It is a sad truth in this system that if you have money, you have a better chance. If you have money and connections you might fare better. There are so many people who can’t afford to take the system on, on any level.”

[superquote]My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime.[/superquote]

My organization, Indiana Families United for Juvenile Justice, had a panel discussion at Purdue University on February 28th, 2013. Grace Bauer of Families For Justice was there, and Karen Grau, Producer of MSNBC’s Young Kids Hard Time, attended. She has met Anthony and she has said how much she likes him. She said he is quiet, and very nice. Those words mean the world to my family. Mark Clemens from Chicago attended. He spoke about being in prison since the age of 16, 28 years for a crime he did not commit. His strength gives us strength. In April I will be attending the JDAI National Inter-site conference in Atlanta, Georgia. Attending will be 180 sites from 39 states and over 700 Juvenile Justice System folks. I am doing what I can to help other families. To be for them what I didn’t have when we started this. Grace has been and is always there for me. I wouldn’t have made it without her. She keeps me hanging on. She tells me, “You can’t let em’ beat you down.” We want to make a manual for other parents and families that are going through this. It’s a complex, often shadowy thing, the juvenile justice system. For many of those involved it’s basically inaccessible. If you don’t have a computer, don’t have internet, you can’t look things up or communicate with others in your position. Having a network is key. Every time something changes in Anthony’s case I email and text everyone to get more advice and information. There is so much I don’t understand.”

[superquote]Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now.[/superquote]

Our whole family life has been turned completely upside down. It’s so rough right now. My granddaughter, Anthony’s little sister, hasn’t been getting enough attention from us. She got lost in all of this. She told one of her friends at school about the whole thing and the parents of the friend forbid their friendship. So she just holds it in, doesn’t tell anyone for fear of reprisal. I have started homeschooling her. She was being bullied. I woke up one morning and realized that whatever energy I had left needed to go towards helping her. She sees a counselor now. At first she didn’t want to visit Anthony, she was scared and so young. But now she visits. We bring in all the kids: the cousins, my 3-year-old grandson, Anthony loves him. Some people question why we bring them in. But they have a right to know each other. He didn’t do anything wrong. Grace [Bauer, of Justice For Families] says you have to do things however you see fit, whatever works for your family. Anthony loves the kids. He talks about driving a car and having kids of his own someday.”

After The Sentencing

“We had a Writ of Cert that was reviewed and denied by the Supreme Court on November 30th. Getting the Writ cost us $8,500.00. My daughter already sold her house, so she sold her car. This should be a right for EVERYONE. It should not be this cost-prohibitive. At least we have these things to sell. It is a sad truth in this system that if you have money, you have a better chance. If you have money and connections you might fare better. There are so many people who can’t afford to take the system on, on any level.”

[superquote]My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime.[/superquote]

My organization, Indiana Families United for Juvenile Justice, had a panel discussion at Purdue University on February 28th, 2013. Grace Bauer of Families For Justice was there, and Karen Grau, Producer of MSNBC’s Young Kids Hard Time, attended. She has met Anthony and she has said how much she likes him. She said he is quiet, and very nice. Those words mean the world to my family. Mark Clemens from Chicago attended. He spoke about being in prison since the age of 16, 28 years for a crime he did not commit. His strength gives us strength. In April I will be attending the JDAI National Inter-site conference in Atlanta, Georgia. Attending will be 180 sites from 39 states and over 700 Juvenile Justice System folks. I am doing what I can to help other families. To be for them what I didn’t have when we started this. Grace has been and is always there for me. I wouldn’t have made it without her. She keeps me hanging on. She tells me, “You can’t let em’ beat you down.” We want to make a manual for other parents and families that are going through this. It’s a complex, often shadowy thing, the juvenile justice system. For many of those involved it’s basically inaccessible. If you don’t have a computer, don’t have internet, you can’t look things up or communicate with others in your position. Having a network is key. Every time something changes in Anthony’s case I email and text everyone to get more advice and information. There is so much I don’t understand.”

My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime. These are children. They cannot drive, cannot vote, cannot make adult decisions but they can be tried as adults and can receive sometimes even longer sentences than adults for the same type of offences. When we used to visit, Anthony would sit there and say, just tell them I didn’t do it. He tells us he will do whatever it takes; he just wants to come home. Before this, Anthony was beginning 9th grade. In December he celebrated his 5th birthday in prison.

[superquote]He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?[/superquote]

He tells me I feel like I’m 15. I don’t feel like I’m any older. How could he not feel this way? He’s frozen in time and hasn’t been in the world since he was 15. Anthony is in a good program at his prison. He earned his GED and is starting college classes. Because of this program he was able to order rotisserie chicken last week. He told us his tears just came rolling down his face when he bit into the chicken. It breaks my heart that he has lost so much. He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?

My grandson is innocent. But even for kids who did do something wrong, 60 years is a lifetime. These are children. They cannot drive, cannot vote, cannot make adult decisions but they can be tried as adults and can receive sometimes even longer sentences than adults for the same type of offences. When we used to visit, Anthony would sit there and say, just tell them I didn’t do it. He tells us he will do whatever it takes; he just wants to come home. Before this, Anthony was beginning 9th grade. In December he celebrated his 5th birthday in prison.

[superquote]He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?[/superquote]

He tells me I feel like I’m 15. I don’t feel like I’m any older. How could he not feel this way? He’s frozen in time and hasn’t been in the world since he was 15. Anthony is in a good program at his prison. He earned his GED and is starting college classes. Because of this program he was able to order rotisserie chicken last week. He told us his tears just came rolling down his face when he bit into the chicken. It breaks my heart that he has lost so much. He missed his freshman year, his freshman dance, his prom, getting his driver’s license. What more must he lose out on before he is allowed to come home?